April 4, 2012

'The Temperamentals' relives gay activism's earliest days

Jonathan Russell Clark READ TIME: 7 MIN.

Generally, we think of the Stonewall riots as the first act of the gay rights movement. Police raided the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village, as they often did to gay bars. Riots ensued, marking the first response to anti-gay laws in America. Before 1969, in our collective memories, homosexuals were closeted, hidden, euphemized or persecuted. While this is basically true, there were a few individuals before then who were open and, what's more, organized.

One such man was Harry Hay, who, in many ways, has been forgotten by history. In 1950, Hay founded the Mattachine Society, a gay political group designed to organize the socially marginalized homosexual community.

Now, the environment during this time was still euphemistic, for Hay originally wanted to call his group "Bachelor's Anonymous," and the first meeting was listed under the name "Society of Fools." Homosexuals, in general, were often referred to as "temperamentals." But euphemistic or not, it was still an incredibly daring move to attempt to unite such a deeply controversial group.

A visionary

So why has history ignored Hay?

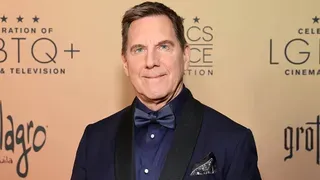

"To the end of his day," says Jon Marans, author of the play "The Temperamentals," at the Lyric Stage Company of Boston through April 28, 2012, "he was far too left for the mainstream gay world." Hay was a committed communist and, according to Marans, "a visionary and a revolutionary."

"He was joyously unapologetic about who he was. He wasn't whiny or complaining. It was your problem if you couldn't accept him."

When I confessed that I didn't know who Hay was, Marans told me that before working on the book for the musical "Legacy of the Dragonslayers," Marans hadn't heard of him either. "There was a chapter in 'Coming of Age' [the Studs Terkel book upon which 'Legacy...' was based] called 'The Others.' It had this incredible interview that he did from the 80s."

Difficult to work with

Marans was so taken with this charismatic figure that he put him into the play. And people loved him. "He stole the show."

This set Marans on a journey to work on a play about Hay, but he had to find the story. After much searching, Marans found it in Rudi Gernreich, a fashion designer and Hay's lover. (Gernreich's futuristic designs made him a controversial figure in the fashion world, most notably for his invention of the monokini or "topless" swimsuit and the "thong" in the 1960s.)

"Hay was so strong-willed and difficult," explains Marans, "a lot of people didn't want to work with him." People at the time found the idea of a gay organization understandably risky, all the more so since it was "basically formed by a bunch of communists."

"In the beginning, the hard thing was finding anyone who had the balls to do this," Maran says. "It wasn't until he fell in love with Rudi--social, charming, the opposite of Harry--that people began to join. The society wouldn't have happened without Rudi."

Most exciting time

"The Temperamentals" began in New York in 2009, where it slowly escalated from a small theater to a much larger one, eventually winning a Drama Desk Award for Best Ensemble. Now, two years later, the play has merited productions all over the country.

"This is the most exciting time I've ever had in theater," Maran says of the time since "The Temperamentals" premiered.

And that is saying something. Marans, in his career, has had some very exciting things happen to him. For example, his 1996 play "Old Wicked Songs" was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and has been produced internationally. He has received numerous other awards for various works and has worked in film and television.

Nobody talked about homosexuality

During its original New York run, they had what were called "militant Mondays," which were talkbacks with the cast and crew. Marans would talk to many of the people who joined them for talkbacks, one of which was Massachusetts Representative Barney Frank. "He was astoundingly forthright about some personal things. Quite touching and surprising."

Based on some of these talkbacks--as well as working with actors and directors--Marans reworked and rewrote. "I tend to rewrite an enormous amount." And now we have the final work, the definitive version, fine-tuned and retooled over many productions and many months.

Before we finished talking, Marans began to discuss an episode of the celebrity quiz show "What's My Line?" from 1955, in which Fred Astaire was the mystery guest. A contestant, trying to discern if the guest is male or female, asks, "When you walk down the street, do men whistle at you?" The audience roars with laughter. Fred Astaire acts mock-offended.

No one talked about homosexuality

"[Homosexuality] was something that everybody got but nobody talked about. Everyone watching that show got what that meant, but no one said it. It was just something being discussed that was very taboo, and yet not being discussed."

It was a very different world then, where publically everything taboo was kept quiet, slyly referenced at most but never directly spoken about, but we should take it as a testament to people like Harry Hay and Rudi Gernreich that it now is.

The Lyric Stage Company of Boston's production of "The Temperamentals" continues through April 28, 2012 at the Lyric Stage, 140 Clarendon Street, near the Back Bay T station. For more information, visit the Lyric Stage Company website.