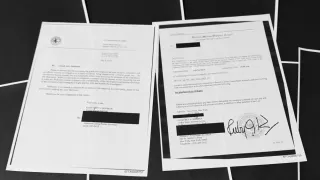

March 13, 2024

Arkansas Stops Offering 'X' as an Alternative to Male and Female on Driver's Licenses and IDs

Andrew DeMillo READ TIME: 2 MIN.

Arkansas will no longer allow residents to use "X" instead of male or female on state-issued driver's licenses or identification cards, officials announced under new rules Tuesday that will also make it more difficult for transgender people to change the sex listed on their licenses and IDs.

The changes announced by the Department of Finance and Administration reverse a practice that's been in place since 2010, and removes the "X" option that had been used by nonbinary and intersex residents. The agency has asked a legislative panel to approve an emergency rule spelling out the new process.

Republican Gov. Sarah Huckabee Sanders, who last year signed an executive order banning gender-neutral terms from state documents, called the move "common sense."

"As long as I'm governor, Arkansas state government will not endorse nonsense," Sanders said in a news release.

The move is latest among Republican states to legally define sex as binary, which critics say is essentially erasing transgender and nonbinary people's existences and creating uncertainty for intersex people – those born with physical traits that don't fit typical definitions of male or female.

"This proposed policy seeks to erase the existence of non-binary and intersex Arkansans by denying them identity documents that reflect their true selves, forcing them into categories that do not represent their identities," the American Civil Liberties Union of Arkansas said in a statement.

At least 22 states and the District of Columbia allow "X" as an option on licenses and IDs. All previously issued Arkansas licenses and IDs with the "X" designation will remain valid through their existing expiration dates, the department said. Arkansas has more than 2.6 million active driver's licenses, and 342 of them have the "X" designation. The state has about 503,000 IDs, and 174 with the "X" designation.

The changes would also make it more difficult for transgender people to change the sex listed on their licenses and IDs by requiring an amended birth certificate be submitted. Currently, a court order is required to change the sex listed on a birth certificate in the state.

Under the new rules, the sex listed on an Arkansas driver's license or ID must match a person's birth certificate, passport or Homeland Security document. Passports allow "X "as an option alongside male and female. If a person's passport lists "X" as their gender marker, the applicant must choose male or female, Finance and Administration spokesman Scott Hardin said.

DFA Secretary Jim Hudson said in a statement that the previous practice wasn't supported by state law and hadn't gone through the public comment process and legislative review required by law.

The policy comes after Arkansas has enacted several measures in recent years targeting the rights of transgender people, including a ban on gender affirming care for minors that's been struck down by a federal judge as unconstitutional. The 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals is scheduled to hear oral arguments next month in the state's appeal of that decision.