Jul 27

Bay Area International Deaf Dance Festival showcases artists from around the globe

Myron Caringal READ TIME: 1 MIN.

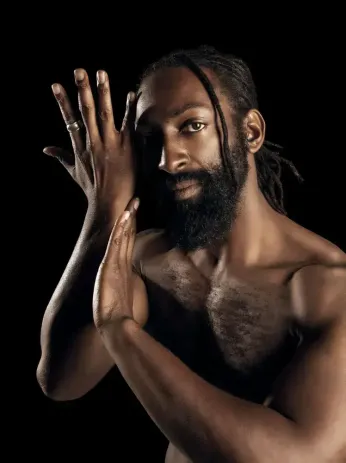

When Antoine Hunter first launched the Bay Area International Deaf Dance Festival (BAIDDF) in 2013, he planted what he calls a small seed. Thirteen years later, he said, “It’s grown into a big redwood tree.”

The annual event, running the second weekend of August, showcases deaf and hard-of-hearing artistry from around the globe, while exemplifying what true cultural access looks like. A project of Hunter’s Urban Jazz Dance Company, BAIDDF is unapologetically deaf-led, community-driven and joyfully intersectional.

“It feels really amazing and bigger than me,” said Hunter in an interview with the Bay Area Reporter. He also goes by the name Purple Fire Crow. “It’s really a community festival now, not just a company festival.”

This year’s lineup reflects that growing international scope. Dancers and performers are coming from across the Americas and Africa, including a long-anticipated debut by Okavango Deaf Polka Dancers, a group from Botswana, South Africa.

“They’ve been trying for years to come, and they finally got their visas approved,” Hunter said. “That’s five artists traveling all the way here. It’s huge.”

Also joining the festival are Corporacion Cultural Y Artistica-Sin Limites from Colombia, known for their folk dance rooted in Colombian traditions, and Deaf Dance Beyond Collective from Jamaica. They’ll perform alongside The Wild Zappers from New York and San Francisco’s own Urban Jazz Dance Company.

But the draw of BAIDDF isn’t about who’s on stage. It’s how they’re seen and heard. Performances feature American Sign Language, International Sign, Colombian and Jamaican Sign Languages, with simultaneous spoken English and Spanish voicing. Audio descriptions and tactile sound systems, like a vibrating device placed under the stage, are also part of the experience.

“It feels like a California earthquake in rhythm,” Hunter laughed.

“Growing up, I always wanted my family to experience inclusive performances,” he said. “Many deaf people have hearing parents, or deaf artists have hearing children. So, where’s the place where hearing and deaf people can all enjoy an event together?”

BAIDDF answers that question by putting deaf artistry at the center in both its representation and its leadership.

“Most festivals are hearing-led, and most are led by white [people], too,” Hunter said. “This is different. It’s deaf-led. Black-led. Two-spirit-led.”

Hunter’s intersectional identity as deaf, African, indigenous, disabled, and two-spirit is embedded in every layer of the festival.

“I can’t divide that,” he said. “When you see my dance company of nine dancers, you will see something that says ‘This is being created by a Black person, this was created by a two-spirit person.’”

His choreography is steeped in ancestral memory and community healing. But for Hunter, the work is bigger than aesthetics.

“It’s in my DNA to serve the community,” he said. “To bring their stories to the stage so we can recognize the people who have to be heard. It saved my life. It has the power to bring the community together. I think passionately about that”

BAIDDF’s impact is tangible, and it’s led some to host their own festival centered around deaf and hard-of-hearing folk.

Hunter remembered a deaf attendee who was in disbelief that BAIDDF was completely deaf-led, but Hunter reassured them.

“They went back to South America and they Instagrammed me a few months later,” Hunter said. “They became the director of their own dance theater.”

This year’s festival will also feature a panel at the San Francisco Disability Cultural Center to discuss what it means to be a deaf artist across cultures and contexts.

“We want to talk about identity, how it feels to show your identity in public,” said Hunter. “Some artists stay quiet at other events. But here, they feel open. I want to keep that spirit of being open alive.”

That sense of openness is part of why the festival matters for deaf artists and hearing audiences unfamiliar with deaf-led spaces. Hunter is clear: everyone is welcome, and everyone will be able to engage.

Still, he wants people to understand the work it takes to make that inclusion real.

“They say I make it look easy but it’s not,” he said. “It’s not easy, and I know it looks very dreamy.”

When first pitching this festival, Hunter was rejected by venues that didn’t believe deaf artists could deliver a full program. Some even questioned whether there was an abundance of deaf dancers.

“And I said, ‘Yes, I’ve seen them.’”

Now, the same theaters that once turned him away are asking to host. But Hunter is careful.

“Is their space accessible to deaf people? Are they willing to learn how to listen to deaf people?” he asked. “Because sometimes they want to do everything themselves without asking, ‘What do deaf people need?”

His hope for audiences is simple: come ready to listen.

“Just because you can hear doesn’t mean you know how to listen,” he said. “My work is about deaf culture, but you don’t have to be deaf to hear the message. Don’t be deaf to the message.”

Urban Jazz Dance Company’s 13th Annual Bay Area International Deaf Dance Festival, $17.85-$44.52, Friday-Sunday, August 8-10, Dance Mission Theater, 3316 24th St., http://www.realurbanjazzdance.com