August 10, 2025

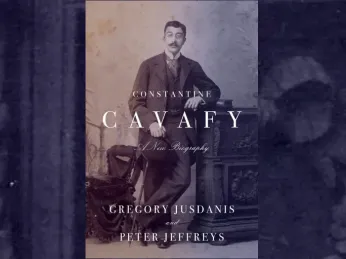

‘Constantine Cavafy: A New Biography’ – An exemplary, long-awaited study reveals the man behind the verse

Tim Pfaff READ TIME: 1 MIN.

The more or less undying fascination with the poetry of Constantine Cavafy (1863-1933), largely but hardly exclusively by the gay audience he addressed both expressly and subliminally, has not produced a full, reliable biography until now. “Constantine Cavafy: A New Biography” (Farrar Straus and Giroux), by Gregory Jusdanis and Peter Jeffries, paints a portrait that extends to the edges of the canvas without using a broad brush.

Their scholarship is exemplary, but quietly within it beats an unmistakable affection for their subject, an asset in any biography that stops short of hagiography. In short, the reader learns not only why Cavafy is now regarded as one of the greatest 20th-century poets but also one whose work occupies a prominent place at many bedsides.

Beyond dates and events

It’s not uncommon for biographies of this depth to begin with a bare chronology of dates and their corresponding events. With the prospect of a long biography in the wings (this one weighs in at 418 pages of text, not inclusive of the notes and an exhaustive index), the reader might be tempted to skim here, but in “Constantine Cavafy” there’s a tale –and then some– in those bare facts, and perusing them makes a difference.

Cavafy fans know –if only from his poetry– that Alexandria, Egypt was his true, beloved home. But the family in which he was raised was itinerant, and there’s a tale to tell in accounts of their restless, usually money-related travels, mostly around Europe. The sense of dislocation amid the devotion to a particular place infiltrates Cavafy’s verse.

That said, the authors are not bound by the facts, as reliable as they are. They tell the story in fundamentally reverse order, and arrange their study by themes, not speculative but concentrated in a more extensive and rewarding examination of the evidence. Survivors of multi-volume, “complete” biographies of the subjects will appreciate this ultimately more illuminative strategy.

Setting the record “straight”

The prevailing misunderstanding of Cafavy’s own experience as a homosexual man (the word “gay” was still in the future and in any case would not apply to Cavafy) is that by day he toiled as a menial clerk in Alexandria’s Office of the Irrigation Service to afford him evenings of carnal evening liaisons with younger men, often of social classes beneath his. In fact, these authors assert, he was increasingly “prudish” in his sexual attitudes, if not necessarily in his habits and behavior.

What warrants saying is that he did not, appearances to the contrary, exploit those materially needier young men, as many European celebrities, including artists and other poets, made a now-infamous habit of doing. He shared the experience of personal poverty with them. His contact with them was more sympathetic than ephebophilic, more like Walt Whitman’s and composer Karol Szymanowsky than even of the more sensitive W.H. Auden and Christopher Isherwood, who frolicked in the bars and cabarets of inter-war Berlin.

The longer he wrote poetry, the more Cavafy sublimated the carnality of his social scene, not to disguise it but to find its deeper meaning. One of the things that even present-day, liberated readers can identify with is the struggle to come to terms with his homosexuality while in no way denying, let alone despising it.

The poems and the man

This is not the place to look into the poems themselves. The authors do that splendidly and without pedantic intentions or arid style. What may need saying to the Cavafy uninitiated is that his verse is immediately accessible. This is not to say that the poems, mostly on the short side, don’t yield more at each reading. But they precede the advent of the kind of cryptopoetics characteristic of, say, the largely gay “New York School.” Cavafy’s poems are inviting, not forbidding.

Such as this book comes as an invitation to read or re-read Cavafy’s poetry, written in Greek, run don’t walk to classics scholar and renowned translator’s “The Collected Poems” and “The Unfinished Poems” of Constantine Cavafy (Knopf).

In their biography the authors, who make a probing examination of all things Cafavy, address the matter of his homosexuality in all its complexity. “Even in his later years,” they write, “with his poetic reputation secure, he followed a double strategy of publishing scandalously frank erotic verses while maintaining discretion about his own life.”

“Constantine feared social rejection all his life.” With respect to his milieu, they observe, “Despite the much-vaunted cosmopolitanism of Alexandria, it could not tolerate open and ostentatious homosexuality.” As regards his menial job, they write, “was for him a way of earning a living so that he could pursue his true vocation –poetry.”

For Cavafy the essential liberation was not to express his sexuality openly but to be and remain free to write the verse he felt called to write.

“As a poet, Constantine faced the classical dilemma: Did his duty to art supersede his need to earn a living? … Poverty would be preferable, he noted, to betraying the value of artistic freedom. An author, he argued, who worries about future sales would become influenced by the tastes of the public.”

Despite his opinion that the literature being written in his day was in what the authors call a “sorry state,” he was committed to writing poetry that had a future beyond immediate sales.

If he only knew the often ecstatic reception his work receives a century on, he might have valued his artistic independence even more.

“On the whole,” his new biographers write, “Constantine remained faithful throughout his life to his aesthetic beliefs … At the same time, however, he feared that by middle age, he had compromised the sexual freedom of his youth. In 1905 he “grumbled,” the authors say, that “[the] wretched laws of society … have diminished my work. They have inhibited my expressiveness.”

If only a time machine could reach back to console Cavafy that his poetry would live, be inspirational, and sell.

‘Constantine Cavafy: A New Biography,’ by Gregory Jusdanis and Peter Jeffreys. Farrar Straus and Giroux, 530 pages, $40. https://fsgbooks.com