August 18, 2025

‘A Day Like Any Other’ – Nathan Kernan’s startling new biography of poet James Schuyler

Tim Pfaff READ TIME: 1 MIN.

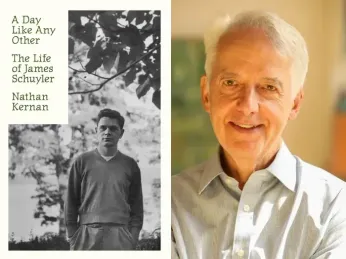

The fact that Nathan Kernan spent three decades writing “A Day Like Any Other” (Farrar Straus and Giroux), which must stand as the definitive biography of American poet James Schuyler (pronounced “SKY-lar,” 1923-1991), speaks to the complexity of his subject.

The Preface recounts Schuyler’s first-ever public reading of his own poetry –at the age of 65– with his audience, many of the artistic celebrities of his time, by all accounts in rapture. It establishes, movingly and from the jump, Schuyler’s importance in and influence on the American poetry scene.

Then, by the second chapter of the biography proper, we learn that “Jimmy” Schuyler was ten pounds at birth, and nearly 20 inches long. The reader, having just emerged from a detailed history of Shuyler’s broken family (he turns up at the Easter Egg Roll on the White House lawn due to his stepfather’s lofty D.C. connections), prepares for the exhaustive while fearing the exhausting. But for a poet who until recently has fallen so precipitously into obscurity to all but a cadre of devoted readers, almost all poets themselves, details matter, and the story told in full is ceaselessly interesting, if sometimes pruriently so.

Pretty is as pretty does

The gods of physical beauty visited Schuyler early on but did not linger. Beyond the usual ravages of aging, Schuyler’s assortment of mental illnesses, six hospitalizations by his own reckoning, his more or less chronic dipsomania (“I’ve been on a bender since I was 16”) his dependence on drugs, prescription and otherwise (“You could hear them rattling in his pockets,” a friend remarked) gradually sent his good looks packing.

“What it all boils down to,” Schuyler wrote later in life, “is to get a light liquor high, throw in the upper of your choice, toke away at the Nepalese Blue Streak Hash, and keep the amyl handy.”

After quitting a diet and returning to heavy cigarette smoking, he had, he said, “gained 800 pounds and now look like something you find glowering in a back alley of Naples.”

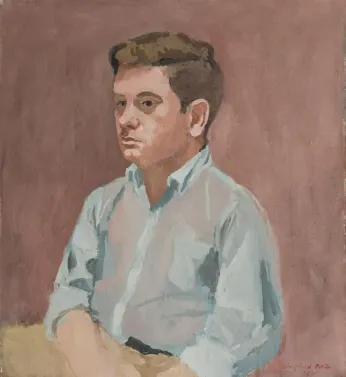

The handsome, twenty-something Schuyler provides the biography’s cover shot. Oil portraits by Fairfield Porter, a bisexual man smitten by Schuyler, further hint at why this chronically shy young man was catnip to many in the poetry circles he inhabited and beyond. The biography tells the rest, again, literally, with pictures.

Sexually, he was promiscuous and credibly insisted he was an expert at fellatio. His progress to S&M was steady, he of course being the bossy M. A stand-out fable of his sexual heyday has it that, when he was staying with W.H. Auden and Chester Kallman when those two were a couple, on a sweltering New York night he pulled the mattress from his lower-level quarters out onto the balcony below, engaged in “rough sex” with his bisexual flame at the time, who wanted to take it inside. Schuyler responded with a resounding, “Don’t stop,” to the bemusement of his illustrious hosts.

He alarmed his friends when he informed them that he was able to finish a long poem because “something happened in my life.” That something was Robert Jordan, whom he met at the Everard Baths and stayed with through the night and into Sunday morning. Jordan, a “big tall hunk” a few years older than Schuyler, was married but in his own way bewitched by his poet find. Regarding their rough sex, at one point it included sewing up Schuyler’s foreskin with dental floss. “As a matter of fact,” Schuyler later insisted, “pain doesn’t hurt; it’s a sensation, like a kiss.”

The diagnosis

Outrageous behavior colored his entire life. Another legend has it that he was taken in by the “bisexual” painter Fairfield Porter and his “understanding” wife Anne –who later commented that “Jimmy” came for the weekend and stayed for eleven years. Once, when the notion of his moving out on his own was floated, Schuyler responded with, “I’ll think about it,” and thought about it for three more years without leaving. It makes for reading as charming as Schuyler himself was said to be, if less so to those who tried to help him.

Over the course of the mental illness(es) he bravely called by that collective name, it became increasingly clear that he was what we now call bipolar. His depressions were cosmic and his manic episodes stratospheric, to the point that their detachment from reality led to tentative diagnoses of schizophrenia. He himself allowed that he got better as he turned from psychoanalytic talk-therapy to a more practical (and typical for the time) medical regimen that included powerful tranquilizers like Thorazine and Stelazine and the additional drugs to counter their side effects. The prescription drugs promoted his weight gain.

What’s consistently notable about the almost overwhelming detail in all matters is that biographer Kernan, who was an associate and friend in the poet’s last years, writes about it all with deep compassion and good humor worthy of his subject. Although he tries to explain it, his choice of calling him both Jimmy (his mother’s nickname for him) and Schuyler is itself baffling in this chronicle of the poet’s far-flung relationships with the artistic luminaries of his time.

Unless your goal is to be the other Schuyler scholar, the dizzying cavalcade of people we still regarded as important might be overwhelming. But there is a careful Index, and you can track whom you choose. At the farthest remove from name dropping, Kernan assures that Schuyler’s lovers, friends, and compatriots emerge as three-dimensional figures, if at times like the ribald guests at a huge, star-studded party.

The poets and the poetry

“A Day Like Any Other” makes no pretense to being a critical study, and Schuyler’s poems make appearances mostly as lodestars in the overall biography, not that they pass through in the least superficially. The saga of this singular man, a “late bloomer” whose introduction to the idea that he might become a poet began with being the typist for Auden, regularly astonishes.

The three long, book-length poems, the last of which remained unfinished, affirm Schuyler’s latter-day debt to the poetry of Walt Whitman. More often, the poems and poem fragments Kernan cites and reproduces on the page attest to the magic of the poet’s penetrating observations, mostly about nature, rendered in verses of ordinary vocabulary, mostly struggling to extend to the end of individual lines and the meaning Schuyler found in matters as seeming simple as line breaks.

“Salute,” one of Schuyler’s first published poems, remained such a totem for him that he included it in most if not all of the collections of his poems, often placing it first, as he did in the first public reading. Resist as his colleagues mostly did being grouped and known as the New York School, the appellation that applied to their run in the 1950s and ’60s has stuck to this day.

The freshness his fellow poets found in Schuyler’s work had and still has everything to do with his deployment of common words to, cumulatively, uncommon ends. You can digest one over your morning coffee and then be haunted by it and its ever-expanding meanings the rest of the day, or of your lifetime, if you so choose.

‘A Day Like Any Other: The Life of James Schuyler,’ by Nathan Kernan, Farrar Straus and Giroux, 503 pages, $40.

https://fsgbooks.com