Aug 26

Guest Opinion: The Joker as queer icon

Samuel Garza Bernstein READ TIME: 5 MIN.

That Cesar Romero was a gay man is not a revelation at this point – scandalous or otherwise. During his years as a studio contract star in the 1930s to the early 1950s, he participated in the dream machine fantasy of dating eligible Hollywood actresses, but looking back at his fan magazine coverage today, it never seems forced or false. He and Joan Crawford laugh uproariously in each other’s arms; he shares a cigarette with Ann Sheridan with a gleeful, conspiratorial gleam in his eye; he winks at Betty Furness with a clear sense of intimacy.

He’s clearly having a blast. Romero is lucky that something he is genuinely passionate about – dancing and nightclubbing – makes him appear as something of a hetero wolf to movie fans. He doesn’t have to pretend as much as other gay stars. Tall, masculine, and graceful, he satisfies the dictates of the era in terms of what being a man is all about. That his ironic nickname is “Butch” is never given much scrutiny. So how does this hunk become a gay icon?

Of course, as far as I’m concerned, dancing with Carmen Miranda is enough to qualify. Miranda dances with many others in her fruity Technicolor fantasies – Wallace Beery, Steve Cochran, Groucho Marx, Dean Martin – but no one else matches her energy level and attitude the way Romero does in “Week-End in Havana” and “Springtime in the Rockies,” though in the latter it’s a group number. Miranda is part of his legacy in other ways. There’s also a censored Fox publicity photo where he is hoisting her in a lift that reveals Miranda is no fan of a Brazilian wax. And a woman in California identifies as the daughter of Miranda and Romero, though without DNA analysis, the claim is impossible to prove or disprove. For the record, she acknowledges Romero’s sexuality – just claims that Miranda brought out his fluidity. And if a gay man is going to sleep with a woman, it does seem appropriate that the woman in question would be Miranda.

Romero is in the business almost 40 years before “Batman” comes along in 1966. In those years he goes from Broadway dancer to Latin lover, from Shirley Temple’s “exotic” kidnapper to the Cisco Kid, from sociopathic gangster to perennial variety show guest star. Always a leading man. Always a romantic possibility. He is almost 60 when he plays the Joker for the first time. His full-bodied, hammy, joyful performance vaults him into pop cultural superstardom. He’s on lunch boxes, school supplies, board games, T-shirts, jigsaw puzzles, and trading cards; he becomes an action figure and a Halloween mask; toys inspired by him include joy buzzers, squirting flowers, and trick guns; and the character goes from being one of many “Batman” villains to rivaling the popularity of the Caped Crusaders themselves.

I believe that letting go of the masculine myth of leading man stardom is really what makes the Joker possible. It’s what lets Romero cut loose so wildly. There are usually a few buxom girls hanging around his lair, but Adam West gets his full attention. It isn’t until the late 1970s, when “Batman” is in afternoon reruns, that I see Romero as the Joker for the first time. I fall in love immediately, and it is the camp element that attracts. This is not just my introduction to the Joker and Romero; it is my first real exposure to live-action superheroes of any kind, leaving me with a sense of the genre being great fun and, more important, as a place that is queer friendly, though I don’t have the vocabulary or sense of cultural identity to articulate it in that way at the time. The only other nascent LGBTQIA+ representation in the media I remember from that era is also camp – with the usual suspects – performers like Charles Nelson Reilly, Paul Lynde, Rip Taylor, and Wayland Flowers and Madame (a phenomenally popular ventriloquist and his garrulous drag queen-like puppet). More serious fare, like “That Certain Summer” and “Boys in the Band,” is not in my childhood experience, and the idea of lesbians, bisexuals, and trans people is not yet on my radar.

I recognize these men as projections of my future self. While I don’t imagine myself growing up and plotting the demise of grown men who wear their underpants outside of their tights, I recognize the humor, the mannerisms, and the undercurrents if not the physicality of the innuendos. And Romero takes no shit. By the end of the first of each two-episode story, he’s always winning. I know he will lose by the end of the second part, but on some level, I recognize that as a fulfillment of the narrative demands of the form rather than as a personal loss for him. To me, he is a winner, and I like that very much. I’m an effeminate kid, thankfully not bullied or particularly singled out, but for a variety of reasons, I don’t feel very powerful. The Joker’s wild abandon is inspiring and empowering in a cockeyed sort of way. It has nothing to do with conforming to anyone’s idea of being masculine, and it has everything to do with proudly letting your freak flag fly.

In 1989, when “Batman” gets its historic reboot, the menace of Jack Nicholson is startlingly different from Romero. By the time of the Oscar-winning performances of Heath Ledger and Joaquin Phoenix, as well as Jared Leto, where the Joker becomes a truly frightening psychopath, Nicholson comes to seem relatively lighthearted, closer to Romero than to Ledger or Phoenix. The camp is mostly gone, but not the queerness. An underlying gender fluidity still informs the Joker through all of the live-action performances, and the character’s erotic obsession with Batman has deepened. With Romero it never had a truly carnal edge. By the time we hit Ledger, Phoenix, and Leto – the character appears entirely pansexual – frankly it’s the most recognizably human part of him that remains in his current incarnation. My original notion of the superhero space being LGBTQIA+ friendly has proven spectacularly accurate – prescient even. Now, Robin, Harley Quinn, Catwoman, and Batwoman are all queer identifying across various media. But Romero got there first, and for me, his lighthearted, gleeful camp performance will always be a part of my own gay coming of age. Hail Cesar.

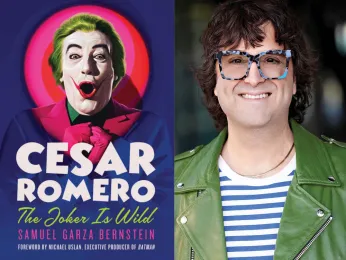

Samuel Garza Bernstein, a gay man, is an award-winning author, screenwriter, and playwright. His latest book is “Cesar Romero: The Joker Is Wild,” which was published August 26 by University of Kentucky Press. Bernstein and his husband, Ronald Shore, have been together for over 30 years and split their time between Los Angeles and Porto, Portugal.