October 7, 2025

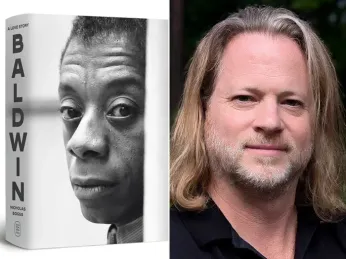

‘Baldwin: A Love Story’ – Stellar writing in Nicholas Boggs’ expansive biography

Brian Bromberger READ TIME: 1 MIN.

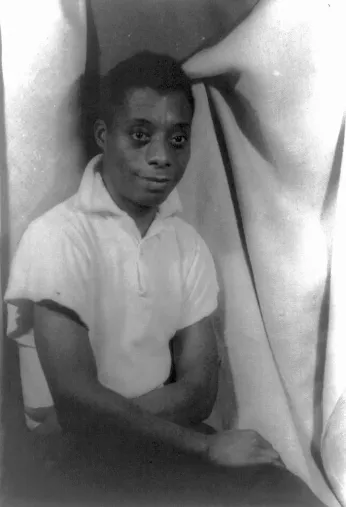

Gay Black writer James Baldwin (1924-1987) seems to be everywhere: TikTok memes, social media hashtags, Raoul Peck’s 2016 award-winning documentary, “I Am Not Your Negro,” Princeton University’s Professor Eddie Glaude bestselling book analysis, “Begin Again, James Baldwin’s America and Its Urgent Lessons for Our Own,” Barry Jenkins Oscar-nominated adaptation of Baldwin’s novel, “If Beale Street Could Talk,” and even Baldwin’s face on a coffee mug.

2024, his centennial year, was the subject of university conferences and fanfare articles in newspapers and magazines. He is the author many university students want to read. This is a remarkable feat, as Baldwin was considered passé when he died in 1987, a civil rights era monument that had been co-opted by white liberals. Baldwin had succeeded brilliantly in the 1960s with his influential essays, but his later work, especially his novels, were largely considered critical and commercial failures.

Why is Baldwin the (not so) sudden rage? It might be fair to say the country and the times have finally caught up with Baldwin. His insights into white supremacy, its connections to misogyny and homophobia, police brutality, and racial relations seem incredibly relevant even if they were written decades ago. He was intersectional before the term was invented.

A quote from his book, “The Fire Next Time”– “At the root of the Negro problem is the necessity of the white man to find a way of living with Negro in order to live with himself,” – is as true in 2025 as it was in 1963.

Life & loves

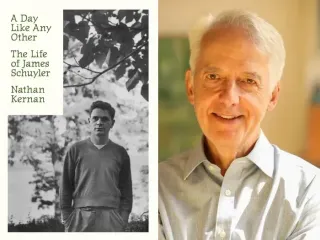

It is fitting that for the first time in 30 years, a definitive magisterial biography has been written, “Baldwin: A Love Story,” by gay independent scholar Nicholas Boggs. The book incorporates new archival material, including unpublished letters, love poems, original interviews, a recovered Baldwin children’s story, and never-before-seen-photographs. Twenty years in the making, Baldwin’s queerness is explored in depth for the first time in a biography.

The book focuses on Baldwin’s four pivotal relationships. Beauford Delaney, a Harlem painter, mentor, and surrogate father, encouraged Baldwin’s creativity and pushed him to move to Paris in 1948. There he met Swiss painter Lucien Happersberger, the love of Baldwin’s life, the muse who inspired his novel, “Giovanni’s Room,” who provided a family house in which to write it.

Then Baldwin fell in love with Turkish actor Engin Cezzar in Istanbul in the late 1950s, while he was working on a stage adaptation of “Giovanni’s Room.” In the 1970s, there was iconoclastic French artist Yoran Cazac, with whom he collaborated on their children’s book “Little Man, Little Man.” All four men provided an emotional grounding and inspiration for Baldwin’s literary work, even dedicating novels to each one.

Baldwin had obstacles from the very start. Born out of wedlock, he never knew who his father was. His stepfather, a Baptist preacher, was emotionally and physically abusive to him, calling him ugly and a sissy, and resented his bookishness. He also hated white people.

It would take Baldwin decades before he could see himself as worthy of love. He never perceived himself as being attractive to other men. Baldwin grew up in the church and started preaching at age 14 at a nearby Pentecostal church. This experience helped him develop his sermonic prose style both in writing and in speaking.

In his elementary school, he was encouraged by a young white schoolteacher Orilla “Bill” Miller, who recognized his writing gifts and took him to theater outings. They remained friends his entire life. He once said she was the reason he couldn’t hate white people.

Leaving high school at 17 before graduation, he moved to Greenwich Village and fell in love with a close friend, Eugene Worth, who jumped to his death off the George Washington Bridge when Baldwin was 22. Earlier, he became involved with a 38-year-old Spanish and Irish racketeer named Billy, with Baldwin later writing, “He fell in love with me and I will be grateful to that man until the day I die.” There was a rape, gay bashings, and arrests for public gay sex.

Bonjour, Paris

These shattering experiences along with his disgust at racism (“the so-called Negro was trapped, disinherited and despised in a nation unable to recognize him as a human being”) and wanting to explore his sexuality, led him to move to Paris in 1948 to start his career as a writer. His favorite author and mentor novelist Richard Wright lived there, plus the city’s reputation as being welcoming to African-Americans attracted him. He had many sexual affairs, possibly including actor Marlon Brando. He didn’t return to the U.S. till 1957.

His autobiographical novel about growing up in Harlem, “Go Tell It on the Mountain,” established his reputation, solidified by “Giovanni’s Room,” even though it was a gay love story between two white men mirroring his relationship with Happersberger. It would take him another two decades before he wrote a black queer love story, “Just Above My Head.”

In the late 1950s he began writing essays to bolster the emerging civil rights movement, culminating in his masterpiece, “The Fire Next Time” which rendered him a leader in the eyes of the public. Boggs interprets the book as how white and Black Americans, much like lovers, come to understand each other and confront the country’s past and present.

Civil rights

Following the attack by Birmingham, Alabama police on Black demonstrators with fire hoses and dogs in 1963, he organized along with other Black luminaries such as Harry Belafonte, Lena Horne, and Lorraine Hansberry, a meeting with Attorney General Robert Kennedy to complain about President Kennedy’s failure of moral leadership. This confrontation was considered a failure as Kennedy seemed oblivious to their demands, however less than three weeks later, President Kennedy delivered a televised speech announcing he was sending a civil rights bill to Congress, which following his assassination, became the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Boggs believes Baldwin deserves some credit for that landmark achievement.

Baldwin wasn’t really close to Martin Luther King, being more sympathetic to Malcolm X and later The Black Panthers, believing they spoke more authentically to Black people in the streets. Similar to gay organizer Bayard Rustin, despite being an effective spokesman for the movement, because of his homosexuality, Baldwin wasn’t allowed to speak at the 1963 March on Washington. Instead, he wrote a speech that was read by actor Burt Lancaster with no acknowledgment they were Baldwin’s words.

Rootless, restless

A frustrated romantic, his quest for love was largely unfulfilled. All of his relationships ended rather bitterly. He was mostly attracted to bisexual men, largely unavailable with wives or girlfriends. Happersberger, Cezzar, and Cazac all married women and had children, though he maintained connections with all of them even after their romance died.

There were long periods of loneliness in a rootless, restless existence, constantly moving residences. He suffered several nervous breakdowns and tried to kill himself at least three times. Boggs writes, “The push and pull of a distant, lost love he perpetually sought to retrieve and could sometimes manage to achieve, at least partially, only to lose it again, was becoming integral to Baldwin’s creative process.” However, alcohol, partying, all-nighters, and continual traveling took its toll.

By focusing primarily on his romantic pursuits, this biography tends to downplay the political aspects of Baldwin’s life. Baldwin’s famous televised debate with conservative author William F. Buckley at the Cambridge Union Society on race relations, rates one sentence (!), an unpardonable lapse, considering it was the subject of an entire book.

As an undergraduate, Boggs discovered Baldwin’s out-of-print “children’s book for adults.” He later tracked down and interviewed Cazac, Baldwin’s last great love. Boggs interjects himself into the biography telling this whole tale. It’s jarring and interrupts the flow into the narrative of Baldwin’s life. It should have been put into a separate excursus or afterward.

Yet, Bogg’s biography makes a strong case for queer authors writing on queer lives. Only a gay man would have thought about organizing Baldwin’s life around his great loves. Boggs argues that Baldwin’s real love was writing, motivated by a moral vision of the equality of all people and his commitment to social justice.

It was Baldwin’s writing that allowed him to free himself from his demons and eventually accept his sexuality. Love was politics for him, with Boggs commenting, “We can understand his whole life through his books. All his novels are love stories.”

For those discovering Baldwin, this book is a goldmine. Previously, David Leeming’s “James Baldwin: A Biography (1994) was the definitive account. Leeming was Baldwin’s straight personal assistant in the 1960s. Bogg’s work is now the authoritative source on Baldwin. A stellar intellectual achievement, it’s the best LGBTQ nonfiction book of 2025.

‘Baldwin: A Love Story’ by Nicholas Boggs. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $36.

https://us.macmillan.com