November 25, 2015

Most States Still Criminalizing HIV

David Crary and Brian Melley READ TIME: 4 MIN.

Charlie Sheen's recent revelation that he's HIV-positive served as a reminder that his home state of California remains among a large group of states with HIV-specific criminal laws that activists consider outdated and that the U.S. Justice Department says should be revised.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, 33 states have HIV criminal laws, generally making it a crime to expose others to HIV or fail to disclose HIV-positive status. Sheen, who says his sexual partners knew of his diagnosis, has not been charged, and there's no indication he would face prosecution under California's laws.

The earliest of the laws - in Florida, Tennessee and Washington state - date back to 1986 when fears about AIDS were intense. Most of the measures were enacted over the next several years, before antiretroviral therapies sharply reduced the risk of transmission and transformed HIV - the virus that causes AIDS - into what is now considered a manageable chronic medical condition.

The laws vary from state to state. According to the CDC, 24 states require people who know they have HIV to disclose their status to sexual partners and 25 states criminalize one or more behaviors now known to pose a low or negligible risk for HIV transmission - such as oral sex, spitting and biting.

In recent years, there's been a growing push by advocacy groups, health experts and others for states to modify or eliminate those laws. Critics have formed task forces in several states - including Colorado, Ohio, Georgia and Tennessee - to lobby for changes and draft new legislation.

In California, a coalition of 14 groups has drafted a bill that would reform several criminal laws, though they are still seeking a lawmaker to lead the effort to enact it.

The overarching theme would be to remove HIV-specific language in several laws to bring them in line with the current understanding of the virus, said Craig Pulsipher of AIDS Project Los Angeles.

The proposed changes would address five laws on the books in California. One, in place since 1939, makes it a misdemeanor to willfully expose someone to a contagious, infectious or communicable disease. Another, enacted in 1998, makes it a felony punishable by up to eight years in prison to intentionally try to transmit HIV through consensual unprotected sex.

California also has laws that target HIV-positive prostitutes and people with HIV who donate blood, organs, tissue, semen or breast milk. Another law adds three years to a prison sentence for exposing a victim to HIV through a sex crime. None of the laws currently requires HIV transmission for a conviction.

In general, the proposed reforms would remove HIV from the language so the laws could apply to all serious communicable diseases. The changes would also require transmission of a disease.

"What this does is eliminate these laws that single out HIV from other diseases," Pulsipher said. "We want to make sure we have statutes that take into account things that may come down the line later that aren't on our radar currently."

The misdemeanor law would be revamped to require that someone intentionally transmit a disease, Pulsipher said.

Requiring proof of intent has made prosecution under the felony law a rarity in California, said Ayako Miyashita, a UCLA law professor.

"Intent makes it harder to bring a case," she said. "It's a step above negligence."

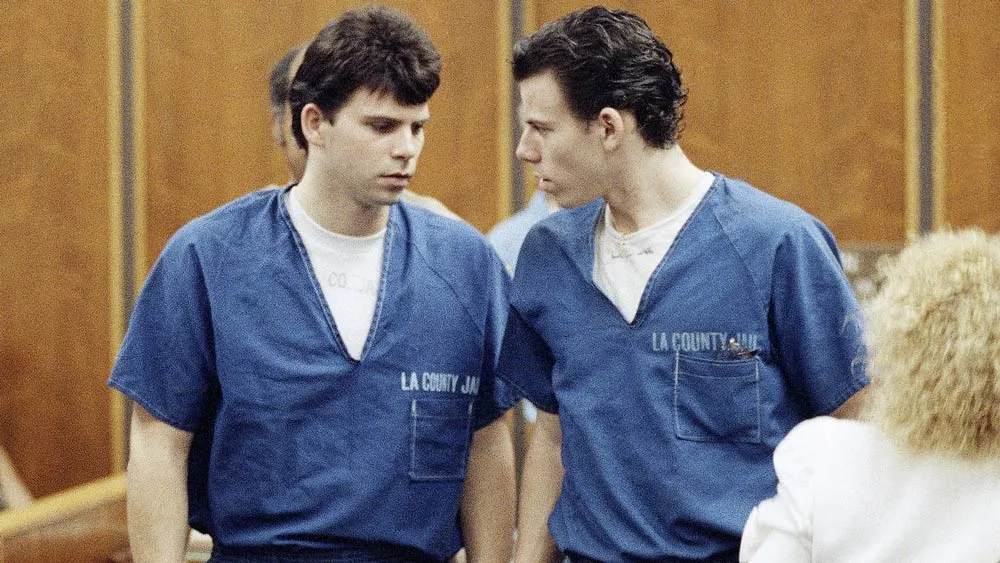

The most recent prosecution in California was in a case in which a man falsely claimed to be HIV-negative and urged his boyfriend at the time to have unprotected sex, according to San Diego city prosecutors. The other man later was diagnosed HIV-positive.

Thomas Guerra pleaded no-contest to a misdemeanor health code violation and was sentenced to six months in jail, the maximum.

The judge called the term a "travesty" and said she wished she could give him more prison time.

On the national level, Rep. Barbara Lee, a California Democrat, has been trying for several years to build support for a bill in Congress that seeks to modernize federal and state laws that can discriminate against people with HIV.

"These laws serve only to breed fear, distrust and misunderstanding," Lee said.

With similar goals in mind, the U.S. Justice Department's Civil Rights Division issued a "best practices guide" in July 2014 encouraging states to reconsider laws that no longer reflect contemporary medical understanding of HIV transmission and thus perpetuate unwarranted stigma affecting HIV-positive people.

Both the Justice Department and the CDC say such stigma can dissuade some people from learning their HIV status, disclosing their status to others, and accessing medical care.

The Justice Department recommended that states eliminate HIV-specific criminal penalties except in two distinct circumstances applying only to people who know they are HIV positive. These instances would be sexual assault where there is risk of transmission, or when an HIV-positive individual clearly intended to transmit the virus.

"While HIV-specific state criminal laws may be viewed as initially well-intentioned and necessary law enforcement tools, the vast majority do not reflect the current state of the science of HIV," said the Justice Department.

Thus far, there's been little legislative response to the Justice Department initiative, though two states took action earlier.

Illinois revised its HIV law in 2012, stipulating that prosecutors would have to prove that an individual specifically intended to transmit HIV to another person. The revised law also says there can be no criminal charges if the HIV-positive person wore a condom during sexual activity.

Iowa modified its law in May 2014, lessening the penalties for people who unknowingly expose someone to HIV with no intention of infecting them. Previously, a person who exposed a partner to HIV without their consent could face up to 25 years in prison.

The change came as attorneys for an Iowa man, Nick Rhoades, were successfully challenging a 25-year sentence imposed on him despite evidence that he had used a condom and had no intent to expose his partner to HIV.

Scott Schoettes, an HIV-positive attorney who is HIV Project Director for the LGBT-rights group Lambda Legal, wishes the pace of change was faster but remains optimistic.

"The legislative process is sometimes slow," he said. "But we are on the road to reform in a number of places."

___

Crary reported from New York