Aug 21

Gonzo Journo William Keck Tells All (and Makes Amends) in Outrageous Memoir

Steve Duffy READ TIME: 14 MIN.

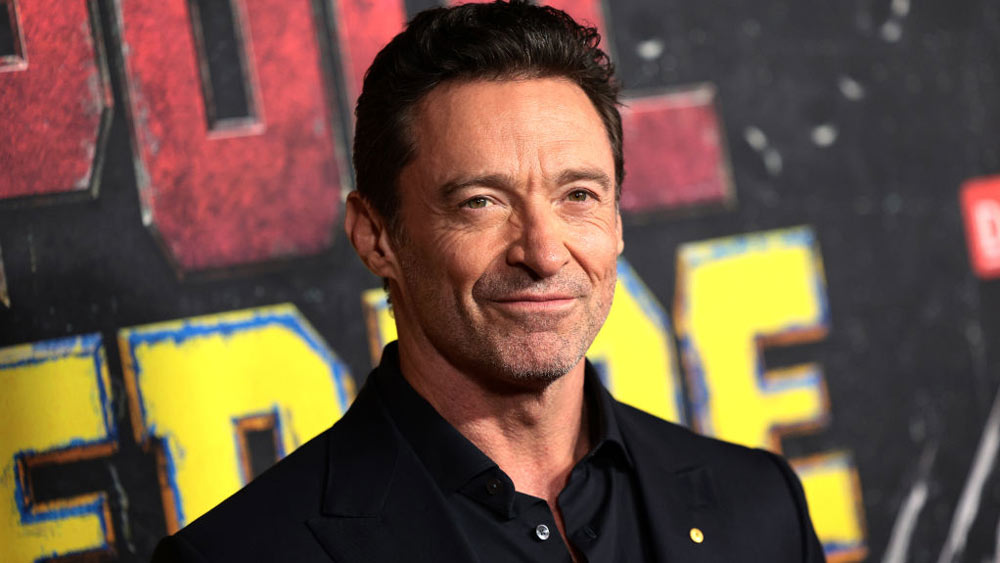

In Variety last month, Michael Schneider wrote that there was no more fearless entertainment journalist than William Keck, who over his extensive career worked at the LA Times, USA Today, and TV Guide before moving on to television production at the Hallmark Channel. But it was his first major job – as a reporter at the National Enquirer – that led Schneider to write Beck "has more outrageous stories than virtually any other reporter I know – many of which he chronicles in his new memoir, 'When You Step Upon a Star: Cringeworthy Confessions of a Tabloid Bad Boy.'"

Keck came to the Enquirer at the height of its success in the mid-1990s and helped give it some respectability. Early on in the OJ Simpson saga, he snuck onto Nicole Brown's family's residential compound for an insider's scoop. When caught, he expected to be thrown out; instead, the family welcomed in and gave him stories over the next few months. It was that kind of ballsy behavior that made Keck a legend with his colleagues and anathema to celebrities.

Keck made many enemies while working at the Enquirer, and did his share of jaw-dropping things. But he reached a saturation point; tired of rummaging through television star's trash or crashing hospital rooms of dying celebrities, he moved on to more challenging (if less adrenaline-pumping) work at USA Today, TV Guide, the Los Angeles Times, People, Entertainment Weekly, and Us Weekly as a staff writer or freelancer. During his post-Enquirer work he helped mend the wounds made during his Enquirer days by producing cast reunion specials for Hallmark's "Home & Family" division, where he worked with talent he once preyed upon.

As Schneider points out, you can't take the boy out of the tabloid, which is certainly good news for readers of his wildly entertaining book, which will no doubt make it to various screen formats in the future. (Keck holds the rights.) Wisely, he saved every asset over his Enquirer career – taped interviews, notebooks, and published work – with hopes of someday turning them into a book. But his goal is more than an outrageous tell-all; it is also therapeutic, because it gave Keck the opportunity to reach out to those he offended earlier in his career and allow them to tell their side of the story. In addition, he tells his personal story of being a closeted gay man exposing the secrets of others at the Enquirer while he feared being outed.

EDGE spoke to Keck recently for a cheeky account of his days in Hollywood reporting for the Enquirer, and what followed.

Source: Instagram

EDGE: Please tell us about yourself.

William Keck: I'm from upstate New York and spent the last 30 years as an entertainment reporter and TV producer. I worked for three years at the National Enquirer in the '90s during the OJ Simpson trial and then at the Los Angeles Times. I was the West Coast entertainment reporter for USA Today for five years. I was a senior editor and columnist at TV Guide for six years, and then I spent seven years as a senior talent producer at the Hallmark Channel's "Home and Family" daytime talk show.

EDGE: As a child, I read that you adopted TV families as your own. Who were some of those families, and why?

William Keck: My dad died when I was five years old, and I was an only child. I would play with the other neighborhood kids outside, and then it was time to go to dinner. They would pair up with their siblings and return to their homes to eat. I pictured them like the Bradys and all the other big TV families like the Partridges, and then I would go home and it would just be me and my mom for many years, until my stepfather came into the picture. I always dreamed about being like the Bradfords from "Eight Is Enough," even the Ingalls from "Little House on the Prairie" – that was my dream. When I moved to LA, my main goal was to meet these TV families, and I did, but while working at the Enquirer I was meeting them at their weddings, their funerals, and in their hospital rooms. It was only years later, while I was working at Hallmark, that I could reunite them for big, two-hour cast reunions, and that was when I felt like I was officially an Ewing, a Carrington, an Ingalls, or a Walton.

EDGE: Tell us about "When You Step Upon A Star?"

William Keck: I conducted over 1,000 interviews with celebrities over the years, and most of them went well, but the stories people seem to want to hear are those that didn't go well. Many of those are from my years at the Enquirer, when I was not invited to interview these people. Like I said, I was sneaking into their private domains, and, as you would expect, that didn't go so well. I was escorted out of John Candy's funeral. I snuck into Meredith Baxter Birney's wedding, and I did that by buying a $5 picture frame from Target. I walked into the reception with the other guests, nodded at the security guards, and my date and I lingered around until the last two place cards hadn't been claimed. We grabbed them and sat at a table next to the minister who had married Meredith and her then-husband, Michael. Then, when it came time for the cake cutting, I just jumped up with the other family members and snapped a picture of the cake cutting, which appeared in that week's Enquirer. There were high-speed chases with Britney Spears and Elizabeth Taylor. A lot of weird stuff, like trying to find a husband for Phyllis Diller, a contest I ran in the Enquirer.

It also gets dark. I talk about my journey and the hypocrisy of being an Enquirer reporter snooping into celebrities' private lives while keeping my secrets from the world.

Source: Instagram

EDGE: What secrets were you hiding?

William Keck: I was deep in the closet. I fell in love with someone and wanted to share this with my friends and family, so I decided to come clean in my own private life, which meant also coming clean in my professional life. At the same time I came out, I quit the Enquirer, and the first person I came out to was Judith Light. I mean, how incredible is that? She is a gay icon and advocate for the LGBTQ+ community. We were in a seminar together – the Landmark Forum – and it was a shocking moment of discovery when we both discovered we were in the same seminar. We were supposed to unleash all of our innermost fears and secrets. She said, "Oh my gosh, I'm in an intensive weekend seminar with a National Enquirer reporter." And I realized I was in a seminar with Angela from "Who's the Boss." So, we had to trust each other, and we did. We both took a leap of faith, and it worked out well. By the end of that weekend, I came out to her, and then, soon after that, I came out to everybody.

EDGE: When writing a story for the National Enquirer, were you told to write them as salaciously as possible? What was the directive?

William Keck: The assignment was to find a source. You would pick up the phone, and it could be a disgruntled nanny, a low-paid hospital employee, somebody at the police department, or people who had vendettas against their exes. You never know who could be calling in for a fast buck.

Sometimes, it was the celebrities themselves who wanted to be in the Enquirer. I write about my adventures with Zsa Zsa Gabor and her husband, Prince Frédéric Prinz von Anhalt. He always wanted to be the Enquirer. He called me up one time to say that he had been kicked out of Bally's health club because the women in the jacuzzi could see his manhood through his white Speedo, so I convinced him to go with me to the Beverly Hills Hotel, and he wore his Speedo. We had a cameraman there, and he shot the speedo dry, and then Freddy went into the pool and came out, and we photographed him wet, and then left it up to the readers to see if there was enough of a manhood issue that warranted him to be kicked out. So many crazy stories like that.

Only once was I beaten up by a celebrity, and that's the only name in the book that I don't reveal. It's toward the end of the book. This male celebrity has multiple Emmy wins for his '90s sitcom. He did not appreciate me showing up at his door and snooping into his business. After the beating, I signed a non-disclosure, but I dropped hints, and instead of showing his face in that chapter, I ran photos of me wrestling a bear. The Enquirer always had us do these insane things; you never knew what would happen that day.

EDGE: Favorite outrageous story you wrote?

William Keck: I was trying to crash Dean Martin's funeral, and so the security guards cleared the cemetery grounds. I was walking the perimeter of the Westwood Memorial Cemetery, and I saw that a neighbor outside the cemetery had a tree that was growing over the wall, so I rented the tree for $500, and the photographer and I were perched up there. We had a perfect bird's eye view of the celebrities arriving, including Frank Sinatra and Rosemary Clooney. I could hear Rosemary Clooney singing Dean Martin standards. I stole Kelsey Grammar's garbage to find out his secrets. I conspired to get Telly Savalas (of "Kojak") a tombstone. He had been buried in an unmarked grave, so I pretended to be somebody, and I arranged to have his tombstone installed, and we got photos of that. Those are just a few. There are so many more.